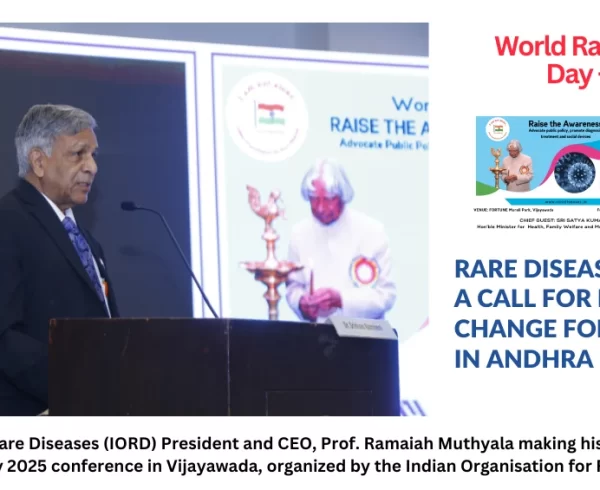

(This article is written by Prof Ramaiah Muthyala, IORD CEO & President and first appeared in the portal Pharmaclick.co.in in its blog section. The original article can be accessed here)

Recent fundraising efforts by some desperate parents of Pompe disease (Glycogen storage disease type II) to buy expensive medicines and prominent associations raising funds via crowdfunding for a child with SMA brought memories of many rare disease patients we have seen in our 20 years of service to the rare disease patient community in India.

To name a few, Rama with MPS VI, also known as Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome, Samara with Alexander leukodystrophy, Shekar with Congenital Ichthyosis’ Saila with Leber Congenital Amaurosis, Asan with Congenital Insensitivity to Pain with Anhydrosis (CIPA), Jacob with Friedrich’s Ataxia, and a whole bunch of tribal community from Dhunaguri village in the state of Assam with Huntington disease and many other rare diseases have neither diagnosed nor named.

While rare diseases affect less than 1 in 2000 people, there are many individual rare conditions, cumulatively everywhere, and a few hundred patients per disease. At least 6% of people live with a rare disease, equating to 300 million patients globally and 90 million in India. 80% of rare diseases are genetic disorders and often are undiagnosed. They are nameless and medical refugees without a home or state. Only 5% of rare diseases have treatments, and approximately 400 orphan drugs are known for more than 7000 rare diseases.

Drugs for some rare diseases are super expensive and unaffordable. Currently, APIs of all generic orphan drugs are manufactured in India and are all exported. Unfortunately, none are made available to Indian patients. Most orphan drugs are inaccessible to patients due to cost, availability, and sustainability. Recently, (2023) MoH&FW has been negotiating affordable prices for patented orphan drugs from multinational companies.

In India, currently, orphan drugs are imported in small quantities at a very high price. It is good news to the patients that the government of India exempted orphan drugs from import duty and GST.

Although one could take advantage of US Orphan Drug Act 1983 incentives – market exclusivity, tax breaks, user fee exemption, clinical trial grants, etc., they apply to the discovery of new drugs only. These incentives do not apply to Indian pharma as they are primarily generic drug manufacturers. Therefore, we believe the Indian pharma industry should have incentives specific to us. We suggested (2020) through the Bulk Drug Manufacturing Association of India (BDMA) a set of incentives to encourage generics and small companies to take up the manufacturing of orphan drugs in India.

Most current manufacturing units are geared towards common bulk drugs in large quantities. The volume of orphan drugs is much smaller than nonorphan drugs. The orphan drug manufacturing involves multistep processes and needs specialized equipment and newer technologies.

Therefore, capital investment for specialty manufacturing units needs to be established. Research for orphan drugs needs resources to focus on skills development. We appreciate the recent (2023) announcement of pharmaceutical research and innovation promotion through academia and industry collaboration from the Govt. of India’s dedicated funding for rare diseases research.

Irrespective of the quantity of orphan drugs, the cost of R&D is identical to the standard drugs running into millions. In this context, production-linked incentives (PLI) schemes should not be looked at in isolation; instead, they should make it part of the big picture of drug manufacturing to treat all rare diseases. The manufacturer of orphan drugs should be incentivized with tax breaks and special subsidies, particularly for biologics, as they are low-volume and high-priced orphan drugs.

We propose that the government creates schemes for guaranteed purchase programs at a fair market price, and grant-in-aid programs to support small and medium-sized pharma companies. The government should encourage academic institutions, universities, and research labs to develop the required skilled workforce for safer, economical, and greener processes.

The rare disease community is scattered throughout the country. Lack of patient information hinders the industry’s business plans. Therefore, in parallel, patient support groups and patient registries should be promoted and prioritized.

In 2017, MoH&FW drafted the National Health Policy for Rare Disease Treatments. Since then, significant activities have taken place at the government level. For example, the Indian Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1945 was amended to include “rare diseases” and “orphan drugs.”; Production-Linked-Incentives included orphan drugs; rare diseases are eligible for Corporate Social Responsibility funding; clinical trial rules have been modified; preventive strategies have been initiated selectively for some blood disorders; alternate therapies – AYUSH system of medicine – are encouraged, Orphan drugs are exempted from import duty; rare diseases are included in the newly drafted medical device policy, and were included in the national health schemes.

Despite the incentives and developments mentioned above, pharma is not making reasonable attempts to reach the expectation of “Make in India” regarding orphan drugs. Most rare disease patients, drug manufacturers, and other concerned stakeholders are unaware of these incentives and accomplishments. The available information is scattered among ICMR, CDSCO, DoP, MH&FW, and other departments and is hard to find. The obstacles are even more significant for developing biological products. The demand for orphan drugs for national and international consumption is expected to increase. Patients’ needs are typically unmet in the current pharma setting.

Further, many academic and industry people are unaware of the problems associated with rare diseases, govt incentives, and gaps in the basic knowledge of rare diseases and orphan drugs; finding the existing information is quite challenging for them. In the country, there are very few experts on rare diseases. It is an identity crisis that lacks recognition for rare diseases and not a lack of information. The information is buried under the voluminous information of common diseases as it is the focus of our pharma industry.

In early 2022, we suggested a dedicated Office for Orphan Products (OOPD) to fill the above unmet needs. A dedicated office answers questions about orphan drug designation, rare pediatric diseases designation, humanitarian use device designations, etc. It serves the pharma, biotechnology, medical device industry, patients, policymakers, and drug regulators. The function of this office is not limited to the above; the other functions of this office are to evaluate products such as drugs, biologics, devices, or medical foods that show promise for the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases, to mention a few. It is a one-stop shop with no other accessible sources.

The OOPD received positive comments from the Ministry of Pharmaceuticals, NITI Aayog, Pharma associations, and pharma companies. In support of such an office, letters of support from heads of many Indian pharma companies were sent to the drug control general of India. Further, new opportunities encourage investments in setting up new manufacturing units for orphan drugs in India. This situation opens excellent prospects for Indian Pharma to receive the reputation as a pharmacy bowl for orphan drugs as well.

A little over two decades ago, the Department of Pharmaceuticals was created (2008), separating from the Department of Chemicals and Fertilizers. Its creation gave an identity to pharmaceuticals and provided a greater focus for the growth of high potential to the pharmaceutical industry. Today pharma contributes 4.5% to the GDP, making it a strategic industry for the nation, earning a net foreign exchange of more than $10 billion annually. Increased accessibility to affordable drugs has been a critical enabler in lowering India’s disease burden and helped reduce the treatment costs of many life-threatening diseases.

Conclusion: A dedicated office for rare diseases and orphan drugs plays a pivotal role in the Indian pharma industry and national economy and lowers the disease burden in the country. It gives an identity for rare diseases without getting lost in the complex system of CDSCO, which already has several divisions such as new drugs, medical devices and diagnostics, biologicals, cosmetics, etc., as separate cells; OOPD will be another division.